“Is the cup half-full or half-empty?”

It’s a silly question that presumptuously assigns someone as being psychologically positive or negative minded based on his/her answer. But, it provides an insight to how humans perceive. If we’re being honest to the question, our immediate reaction is always going to be ‘half-full’. That is because we always see the water first. The state of ’emptiness’ only exists in the context of a container. Furthermore, the cup being ‘half-empty’ is only valid if water exists. You could argue that the same is true vice-versa, that ‘half-full’ appropriates if the counterpart is filled with air. But, we don’t readily see air. We don’t perceive ‘void’. To perceive something as a void, the context (or the containing cup in this case) always needs to be the pretext. In other words, we first perceive the cup half-full, then we can perceive the cup as half-empty. They’re always perceived in that order.

There’s a second layer to this silly question that I appreciate. This is more anecdotal but I think it’s still fun to think about. The question is phrased in an either-or fashion. And, that is reflective of our perceptual experiences, also. It’s reflective of our attention.

(Or perhaps that is more reflective of the fact that humans are limited to a single, linear spatio-temporal space. What I mean is, you can only produce one soundwave at a given time. The soundwave, being a phrase or a sentence, is going to have a subject in focus. Imagine if you had two channels of communication such that we can talk with our mouth and also send messages through radiowaves. The second sentence can have a different subject in focus. You’ll have to divide your trains of thought, but perhaps, then it’s possible to entertain two distinct focus of interest in your head.)

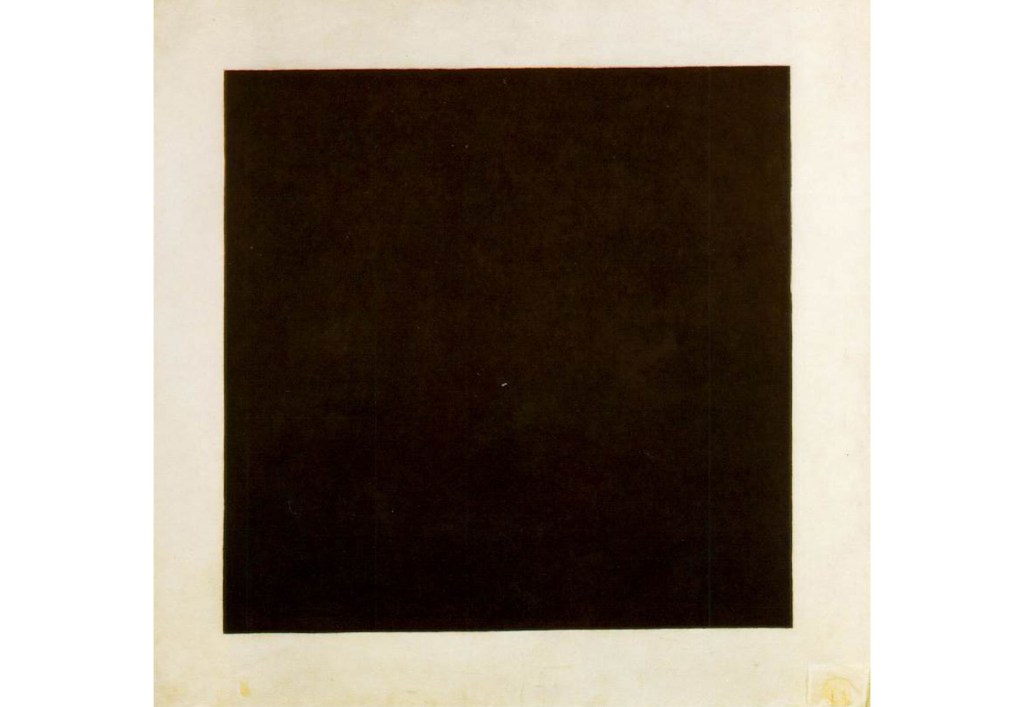

Technically, if the cup is half-full, it also means that it’s half-empty. Then, the question should read “Is the cup half-full, half-empty, or both?” But, that would defeat the purpose of the question because the goal of the question is to probe your perceptual experience. Which, brings me back to ‘Minus White’ and the concept of negative space. It’s okay that our perceptual experience is often limited to positive spaces, or the salient. It’s natural. But, if we want to truly analyze and understand something, we should consider its negative spaces as well. And, negative spaces go beyond our perceptual experiences.

So, how do you apply the concept of negative space into analytical thinking?

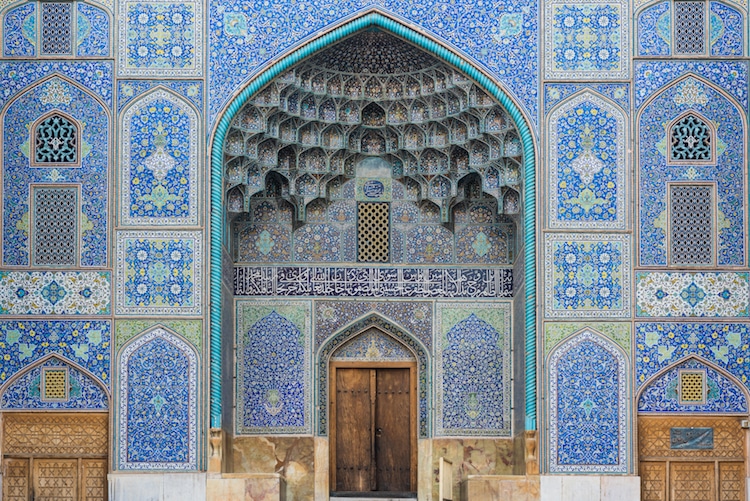

Consider the vaulted ceilings of Sheikh Lotfollah Mosque (the blue, Islamic architecture from the first blog post), the geometrical cutouts on a building façade. The first thing you notice is the explicit cutout. Instead of having a flat surface with an entrance, it caves in. It almost forcibly makes you aware of the negative space.

To truly understand an idea, I believe a first-hand experience is paramount. Now, I’ve never been to Sheikh Lotfollah Mosque nor any mosque for that matter. But, I can still analyze it as I envision in my mind. So, what’re the puzzle pieces I’m looking at, that I’m trying to solve? The first piece is very obvious. It’s the mosque itself. Specifically, it’s the ‘indoors’ of the mosque, permeated by the entrance gate. The second piece is actually not as obvious. It’s the ‘outside’. Immediately out of the mosque, there’s a raised platform, followed by a staircase, and a small park with few ponds. Collectively, let’s just call this ‘outdoors’ for now. Hence, the negative space created by the sculpted inset serves as linking space between indoors and outdoors. But, wait. So, it’s neither indoors nor outdoors?

It’s neither indoors nor outdoors.

Strictly speaking, you could argue that once you have carved a space to expose it to outside, it no longer is indoors. And, you’re absolutely right. But first, let’s move the conversation elsewhere. The continual use of this mosque as an example becomes difficult to analyze because majority of the population is not familiar with this type of architecture. Also, it’s likely that you nor I have been there. So, let’s take a step out and try to generalize this concept: the use of negative space between indoors and outdoors in other buildings. And what you’ll find is that, this concept is actually very common and found in just about every type of building all around the world.

Porches, verandas, halls, and just about any motif that maintains a continuum of roof whilst technically beyond the entrance qualifies for the same function as described for the mosque. Their use may vary, such as reading a book on your porch. (It’d be inconvenient for others to pass through halls and the mosque gates if you decided to take a seat there to read a book. Some people will complain, even if you weren’t directly blocking the entrance. So, some spaces above may have different utilities that compound on top of the negative space discussed.) But, the qualifications that make the negative space in the mosque apply to these spaces as well.

So, you can generalize the concept. It’s much familiar. Now, let’s think about how we refer to these spaces. And you’ll realize that it’s true that we will almost never assign these spaces as indoors in our everyday language. Your mother will say “It’s getting cold. Come back inside.” if you’re out on the porch reading a book in a Canadian October. “Come back inside” suggests that you’re ‘outside’. Here’s another example if you lived in an apartment complex (such as above). Your mailman is delivering your parcel, but you’re not home. He calls you up and asks where you want the package to be placed. You say, “Just leave it outside. It’ll be fine.” (Try formulating a conversation where someone refers to these spaces as ‘indoors’. It becomes very awkward.)

We naturally assign this type of space as ‘outside’. And, we should, because we can’t readily perceive negative spaces. All we can see are physical walls, doors, and windows that divide us from inside versus outside. And, it’s much more efficient to assign words based on this concrete percept in our language. (Whether our perceptual limits actively shape the language or our percept is consequential to the language we choose to speak is a curious question, however.) Functionally, it is an invisible bridge that serve to connect two parts of your local world (e.g. inside your house and your lawn). If we rid of our perceptual experiences, it should be neither indoors nor outdoors.

You can keep extending this train of thought and analyze it. So, our language has determined that whatever is outside of your walls and is exposed to outdoors is ‘outside’. But, what about spaces that make this definition very ambiguous? How about a courtyard within the house? Is it “He’s smoking in the courtyard” or “He’s smoking out in the courtyard”? You’re still within the bounds of the walls after all. You may say, the openness to the sky above makes it no longer shielded by a roof. Okay, so if I put a glass dome, it’s indoors then, right? Or how about the bell tower where you have to climb each noon to ring it? You’re no longer wall-bound, you’re exposed to the outside, but it feels more natural to say “He’s in the bell tower to ring the noon bell”. Or how about the car garage? This one is definitely indoors, right? But, let’s open that garage door and effectively remove one of the four walls. It now functions just like the mosque negative space. So, is it ‘indoors’ when the garage is shut and ‘outdoors’ when it’s open?

I don’t mean to bombard you with puzzles or seem cunning. I just want to share the importance of thinking about negative spaces. And, this isn’t specific to architecture or visual art. It’s the same for music, films, journalism, poems, books, and just about any medium we use to communicate. As long as there’s information made explicit through whatever medium, there’s information that has been made implicit. In journalism, words are essentially carrier of ideas. The person who’s written a newsletter has constructed a well-informed article. He/she has placed it somewhere in the world of ideas. You’ve come to visit this place, and so, you read the words to understand what is being explicitly said. You can, then, ‘read’ what is not being said. For example, let’s say the written piece is arguing for policy changes to fight climate change. It painstaking details the socio-economic disasters that are consequential to harsher climates: decreases in natural resource productions, famine, unprofitable tourisms, increases in wealth gap, unemployment, and so on. What it doesn’t say is the benefits of climate change. (Let’s be clear here that I’m not arguing against climate change.) It sounds absurd, I know. But, you should be able to ask the question nonetheless. Are there any benefits to climate change? Are there people that are likely not going to be affected by climate change? Are there people who’re actually going to profit from disasters? Who and what scenario does climate change work in favor for them? If you believe your cause is genuine, isn’t it also important to explore factors for disingenuity and try to eliminate it? Maybe there’s something there. Maybe there isn’t. But, I think it’s worthwhile exploring that option as well.

So it goes.